Donal McAnallen: The story of barely-known John McKay, co-founder of the GAA

John McKay, the little-known co-founder of the GAA

Saturday marks the centenary of the death of a major but largely forgotten figure in the GAA’s history – John McKay, Down native, founder member and joint secretary, and Cork Examiner reporter.

McKay was the only Cork representative involved in the establishment of the GAA in 1884. He went to Thurles as a representative of Cork Amateur Athletic Club and a reporter. He left as one of three secretaries of the new organisation, alongside the mercurial Michael Cusack and John Wyse Power.

Despite his central role in the development of the GAA in its first two years, over the next century McKay faded so far from the narrative of Ireland’s largest sporting body that even his basic details became hazy. He was described as ‘a Cork man’ and ‘a Belfast man’, but nobody really seemed to know.

In 2009, Kieran McConville of Armagh and I launched into a research mission for the mysterious McKay. After a hunt through newly digitised genealogical records, a public appeal, and the emergence of an old letter held by McKay relatives in Belfast, we traced his roots to the Downpatrick area, discovered that he died in London in December 1923, and found his unmarked grave there.

Then John Arnold of Bartlemy, on behalf of the GAA’s 125 Years Committee, organised the installation of a gravestone memorial for McKay, his wife Ellen, son Patrick Joseph, and grandson Patrick Joseph Jr. The gravestone was formally unveiled at a ceremony in November 2009.

Today’s anniversary provides an opportunity to refresh the story of this GAA founder, with a raft of new research on his extraordinary life and legacy.

John McKay was born in early October 1852, the second of five children born to Joseph and Ann Jane at Cargagh, 3.5 miles southwest of Downpatrick, on the road to Clough village.

This post-Famine decade became even tougher when Joseph, an agricultural labourer, died before 1860 and his 40th birthday, left Ann to rear five children under the age of 10.

Fortunately for John, he received a good national school education and was able to enter the journalistic profession at a time of increasing literacy and growth of print media. He joined the Belfast Morning News staff, which became a daily paper in 1872. He learned Pitman’s shorthand, and served as a proof-reader too.

Most of the McKay family followed John to pursue opportunity in industrial Belfast. By the late 1870s, their home-place was abandoned, and just one sister lived near Downpatrick – Susanna Hanna, with her husband and family, in the parish of Bright.

The other three siblings moved into west Belfast. Two of his sisters were married there in 1880 and 1882; and their mother, Ann Jane, died there in 1883. Alas, the youngest daughter, Margaret (Kelly) died at just 27 in 1885, having already lost two of her own four children. John’s brother, James, ran a shoemaking business on Mill Street in the city centre, raising a family of seven there too.

John sought greener pastures, however. He took a new job as a reporter with the Cork Examiner in April, 1878. These were heady times, and the 1880s would be his defining decade. He travelled all over Munster to cover political events and reported on over 200 meetings of the Land League (being ‘a strong sympathiser’) and the Parnellite Irish National League (of which he was a member).

He joined the Cork Amateur Athletic Club, which had been founded in 1874 and was the foremost track and field club in Munster. Its membership reflected the increasingly nationalist views of the country.

We do not know whether John McKay ever competed in his own right, but his first sporting interest was athletics, and he was first identified as a sports official in July 1884.

When the appointed timekeeper did not show at Cork AAC’s sports meeting at Cork Park in August, McKay stood in. The unionist Cork Constitution remarked on the ‘somewhat peculiar’ times recorded for the 100 yards being ‘attributable to the absence of a reliable time-keeper’. This prompted a spirited defence from his club, including an anonymous letter, allegedly of McKay’s own hand.

From that quick apprenticeship, McKay immersed himself fully in officialdom. By agreeing to go to a meeting at Hayes’ Hotel, Thurles, on November 1, and help to form the GAA, he earned a place in a nation’s sporting history. His speech that evening was one of the most notable contributions, as recorded in his own words:

‘… [T]he formation of the Gaelic Association should only form one step reaching the goal they were all anxious to arrive at — namely, the formation of a general athletic association for Ireland — composed of representatives from all the leading clubs — to regulate the management of all meetings, to frame rules of their own for the government of such meetings, and put an end once and for ever to their being bound by the rules of the English A. A. Association (hear, hear). He … objected to Irish affairs being managed by Englishmen (hear, hear) … .’

Besides writing the most detailed account of the meeting for the Examiner, he was appointed one of three joint secretaries of the GAA, alongside Michael Cusack and John Wyse Power. All three were journalists, sharing the onus of publicising the association as well as its administration.

McKay went on to play a crucial role in consolidating the nascent GAA. With Dublin and Belfast athletics networks aligning primarily to London-based bodies, and coalescing in January 1885 to formal the Irish Amateur Athletic Association as a rival to the Gaelic body, Munster was the principal battleground where the GAA could forge early dominance.

To grasp the scale of McKay’s personal task, we must bear in mind that the GAA was unique in its multi-sports remit. The association not only set down laws for Irish athletics, but also adopted rules for hurling, and codified Gaelic football anew. McKay was on the sub-committee to draw up these rules, alongside President Maurice Davin and his secretarial colleagues.

Many of the men who were trying to take up these sports at a local level were coming from the agricultural labouring class, and had little or no administrative experience. Registration of entries, production of advertisements, enclosure of track and field, and booking entertainment and prizes, let alone the perennial problem of the tackle in football, were among the many new challenges facing novice volunteers around the county.

All of these details, and diffusing knowledge of the new playing rules, were pivotal to the maintenance of order at GAA events and the overall reputation of the association, though altercations were still frequent as participants and indeed rookie referees got to grips with the rules. His letterbox at 4 Elizabeth Place surely bulged.

Hence the immense secretarial work and many trackside timekeeping tasks carried out by McKay at sports meetings across the province helped to raise the GAA’s standard rapidly, while the publicity and constructive criticism of his Examiner reports spurred on fledgling clubs to build and improve.

The weight of his contribution went beyond stopwatch and pen. With Cusack’s forceful personality stoking GAA-IAAA tensions and threatening to lose hearts and minds of sporting enthusiasts, McKay exercised a valuable diplomatic role, being ever-restrained in asserting the GAA’s right to govern as a national body for Irish athletics in the face of criticism from Dublin circles. His levelheadedness was similarly vital to preventing fractious divisions in the GAA’s executive from causing ruin.

Some of the hottest topics were in his own base. The creation of a Munster National Football League, adopting playing rules that diverged from Gaelic football, led to the expulsion of GAA vice-president J. F. Murphy, for his prominent part in this new offshoot. His supporters called a protest meeting for the Foresters’ Hall in Cork in March 1886. Fearing the threat of a deeper split emerging between Cork and the rest of the Gaelic association, McKay went to the meeting along with Cusack and a couple of other national officials.

Being the most familiar GAA official to the Cork malcontents, McKay risked his local reputation by entering that meeting. Cusack had just described the Cork assembly as ‘puny would-be sappers of the GAA’, and had written to Murphy, declaring, ‘Henceforth there can be nothing between us but open and unconcealed war.… Your everlasting foe, Michael Cusack.’

The meeting was reportedly ‘crowded to the doors by a very excitable crowd, and the proceedings from start to finish were of the most disorderly character, … at times … something very little short of a bear garden.’

[sic] Into this breach stepped McKay, to appeal for unity in the association and nationwide: ‘At the present crisis in Irish affairs … there should be calm and temperate talk, and … all tensions should be banished from amongst Irishmen. … The Gaelic Association had never intended that another association should be formed, for they might have five hundred associations all over the country. …They were all Gaelic athletes, and why not all be Gaelic footballers. Some change was, perhaps, necessary in the Gaelic football rules, and would be considered by the association. … [T]here seemed to be an idea that he [Cusack] was the Gaelic Athletic Association. That was not so. (Cheers.) Mr Cusack was not the Gaelic Athletic Association, and never would be as long as he [McKay] was secretary. Mr Cusack … sometimes wrote rather strongly, but … [he] was a strong and vigorous Irishman.’

On the way out, the small party of GAA officials was jostled and roundly insulted on the street. Crucially, though, no drastic plans emanated from the meeting. McKay’s bravery in attending, solidarity with fellow officials, and determination to steer a middle path through the brickbats, were quite selfless. What if he had stayed away? The possibility of Cork secession could have materialised.

Even then, he could only do so much. Cusack embarked on a further writing rampage, and wrote a public letter that appeared confrontational to Archbishop Croke, GAA Patron. This was the last straw for several of the executive. McKay was prompted to write to the Examiner, repudiating Cusack’s letter.

With that, Cusack’s fate was essentially sealed. John Wyse Power compiled a letter of complaint about his fellow secretary’s administrative neglect and ‘insulting’ attitude to colleagues. The Central Council meeting at Thurles on July 4, 1886 would decide Cusack’s fate. Power did not turn up though; Cusack alleged that his accuser had seen him in town, took fright, and left on the next train. That left McKay, the third secretary, with the invidious duty of reading out a complaint by one secretary against another.

No doubt McKay was displeased. He could still admire Cusack’s achievement in conceiving of the GAA, and sense that ejecting him from office was an unnatural act. He may even have suspected ulterior motives: Power and J. K. Bracken, the other key executive figure in the heave, were both IRB men who saw the maverick Clare man as a barrier to the IRB’s quest for control – which they would soon achieve. Nonetheless, McKay did his unwanted duty and read out Wyse Power’s dossier.

Cusack would write later that ‘Mr John McKay … read Mr Power’s statement for Bracken’s packed meeting, in the horizontal voice usually assumed by natives of the north-east of Ireland when they are away from home.’ By a majority vote, including McKay’s raised hand, Cusack was removed as secretary.

AFTER THIS brutal affair, McKay re-evaluated his own position. He may well have realised that life as GAA secretary was only going to get busier as the organisation spread ‘like prairie fire’, with many an unruly blaze still to be controlled. To keep up the burden of travel and trouble involved in managing this national network was ‘too severe a tax upon his time,’ Sport newspaper commented apropos rumours of his pending retirement. ‘Mr McKay was only prevented from resigning sooner by the urgent solicitations of his fellow-officers.’

His domestic duties had mounted all the while. His wife Ellen – née Browne of Tullacondra, Ballyclough, near Mallow – whom he married in 1883, was then well advanced in pregnancy for a third time. Their first child, Joseph James, born in August 1884, had died in infancy. John had also lost several other family members within three years. Such raw human factors are often overlooked in historical examination.

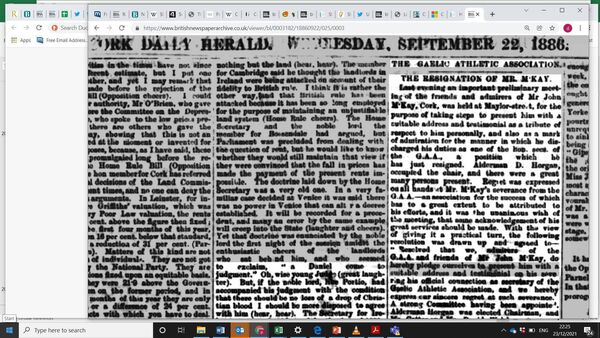

In late August, McKay announced his resignation as a secretary of the GAA, citing pressure of business engagements. Friends and admirers called a meeting in Cork to raise a testimonial to McKay, and opened a subscription fund.

‘The Hon. Sec. of an Affiliated Club’ wrote this letter of tribute to Sport: ‘No words of mine could fully portray the services rendered to the GAA by Mr McKay; no words are needed, as every athlete knows that the GAA has no more efficient officer – no better champion and guardian of its rights.’ John McKay stayed on as an official of Cork AAC up to the early 1890s, both as a committee member and a timekeeper at annual sports.

He remained prominent in journalistic affairs. In May 1889, he gave evidence before the Parnell Commission at the Royal Courts of Justice, London.

After the Parnell split, he became a committee member of the Cork National Society. Formed in December 1891, this society pledged support to the anti-Parnellite cause. McKay became a regular attendee at its historical lectures and social events, and was appointed vice-chairman for 1893.

It was in 1894 that McKay made the bold move to return to Belfast. He was appointed chief reporter for the Irish News.

The newspaper was just three years old, having been set up by Bishop Patrick McAlister, who sprang from the next townland to the McKays in Downpatrick. The paper’s anti-Parnellite leanings of the Irish News accorded with his own.

John was soon noted as joining in the social life of burgeoning middle-class Catholic and nationalist circles in the city. Belfast Young Ireland Society meetings and other lectures became occasional haunts for him and Ellen, alongside eminent MPs, pressmen, business and legal figures.

Nonetheless, it was a restless time for the McKays. Inside five years, they lived in at least four north Belfast addresses, and John worked for four different newspapers.

He switched first to the Northern Star in 1897. Its editor was a Corkman, Timothy McCarthy. For this organ, he wrote a weekly ‘Athletics & Cycling’ column, signed ‘J. McK.’, and provided an enlightening commentary on a north-south rift within Irish cycling. A small print-run did not augur well, and McKay uprooted again, joining the unionist Northern Whig about 1898. By 1899, he was shifting once more, being listed as a reporter for the Dublin Daily Nation while still living in Belfast.

The last-named title tilted John southwards, and it was to Dublin that he and family would move again circa 1900.

The 1901 census finds them living at Blessington Street on the northside. Boarding with them was 22-year-old Shan Ó Cuív of Macroom, who would become a leading Gaelic Leaguer and journalist, and grandfather of Éamon Ó Cuív, TD. Over the next decade, John appears to have worked as a newspaper freelancer, writing for the Irish Independent and Freeman’s Journal.

No record of McKay as a regular sports official thereafter has come to light. He appears to have stood in as a Cork delegate at the 1902 Congress in Dublin, but simply as a one-off. He was also noted as attending Michael Cusack’s funeral in 1906.

McKay was also to the fore on journalistic bodies. In 1891 he had been elected secretary of the Cork Sub-district of the Institute of Journalists. In the late 1890s, he sat on the Ulster district committee.

At one such meeting in 1899, McKay paid tribute to the recently deceased Cork Examiner proprietor Thomas Crosbie as ‘a generous-hearted, considerate employer’. He went onto attend executive meetings of the IIJ’s Irish Association district in Dublin during the 1900s.

The McKays switched cities again, John returning to Munster to work as chief reporter for the Cork Free Press, from around its launch in June 1910. This was an evening radical newspaper published by William O’Brien MP and the All-For-Ireland League, as a moderate nationalist organ and rival to the Examiner. It was beset with financial woes from early on, however. Amid much angst among newspapers’ staff about poor wages and working conditions, John McKay was elected chairman of the newly formed Cork and District branch of the National Union of Journalists in November 1911.

John’s peripatetic career took one more turn in the early 1910s when he moved with Nellie and daughter Johanna to London. They moved to be closer to their sons, who were experiencing very different fortunes.

The elder son, John Paul, had changed his name to ‘Paul Murray’ and become a very big name in the theatrical industry in London. John, then in his sixties, provided clerical support, and was identified in the 1921 census as ‘office manager’ for Murray & Co.

Patrick Joseph, by contrast, had joined the Royal Navy as a youth, contracted gangrene during the Russo-Japanese War, and developed a drug addiction. He enlisted during World War One but was discharged for stealing. His son, Patrick Joseph Jr, died after just ten days in 1917, presumably due to exposure. To the end, he leaned heavily on his parents, who lived at Brixton Hill.

It was there on December 2nd, 1923 that John McKay, GAA co-founder, breathed his last, aged 71. Far from home, he was already a distant memory. Neither the Central Council nor the Examiner even mentioned his death.

Nellie survived until 1949, and a grand 96 years. They were buried at Kensal Green, along with Patrick Joseph (who died in 1929) and Junior.

The 2009 gravestone was not the end of the tale, though. Much else has been uncovered since then.

There is more to tell. Not least, there is how John’s son, ‘Paul Murray’, became involved in a landmark sound films, Elstree Calling (1931), alongside Alfred Hitchcock; but the advent of ‘talkies’ nosedived his boom-bust career and he and his wife had a tragic death in 1949.

There is also the discovery of a second grandson, Denis Paul McKay (1928-2008) – second son of Patrick Joseph. He in turn had two sons, both born in Fulham in the early 1950s. The search for living direct descendants was hoped to be brought to a happy ending for today, but must go on.

For now though, on his centenary, it is timely to revive the memory of this remarkable pioneer of the Irish sporting revolution.

A memorial ceremony in north west London will be held at the McKay grave at St Mary’s Catholic Cemetery, Kensal Green, at 11am today.