Ben Dunne's IRA kidnap, arrest in Florida, and 'thanks, big fella': Episodes in a life lived large

Ben Dunne with his wife Mary on October 22, 1981, shortly after they were reunited after he had been kidnapped and held for ransom for a week by the IRA. Picture: Lensmen/Irish Examiner Archive

Would Ben Dunne’s life have taken a different trajectory if he hadn’t been kidnapped? Would we now be living in a different Ireland, totally oblivious to a culture of corruption that pervaded elements of business and politics for decades?

Dunne was kidnapped by the IRA in October 1981. He was held in captivity for seven days, most of the time hooded, never knowing whether the end was near. When he was released near a remote graveyard in South Armagh, he threw himself into the nearest open grave. The kidnappers gave him three bullets as souvenirs of his captivity, as if he had been on an exotic holiday.

“The first thing I did was get into a grave,” Dunne later recalled. “I looked up and I could see the stars in the sky. I thought, ‘Good God, they could shoot me and throw the earth back in’. So I crawled out of that grave. I didn’t really feel that I was free until I got home a few hours later.”

He was 32 years of age at the time, running a huge cross-border business started in Cork by his father, Ben Senior.

Today, somebody who had experienced that level of terror would seek out counselling to process what had happened and try to come to terms with it. Dunne was back at work within a few days.

That’s how he was reared. From a young age his father had impressed on him the importance of work, the imperative of running a successful business. The values of the family.

Today, Dunne would be described as having had a privileged childhood based on the material wealth that his father Ben had accumulated. His own account of growing up reflected a rearing in which all was geared towards furthering the reach of Dunnes Stores. He didn’t apply himself all that much in school, but his future was

predestined. He would be the next Ben Dunne.

By the time he was kidnapped he was well on the way. And when it occurred, his father dealt with it in his customary manner. The Government insisted that no ransom be paid but Ben Sr decided he would do what had to be done.

A ransom was paid, though denied, and arguably the decision to do so prompted the kidnapping a few years later of the supermarket tycoon Don Tidey, also by the IRA.

Once Dunne was freed, there was never any question of taking a moment to pause or reflect. It was back to work straight away as if nothing had occurred.

In 1983, his father died, having willed him the values and drive to succeed.

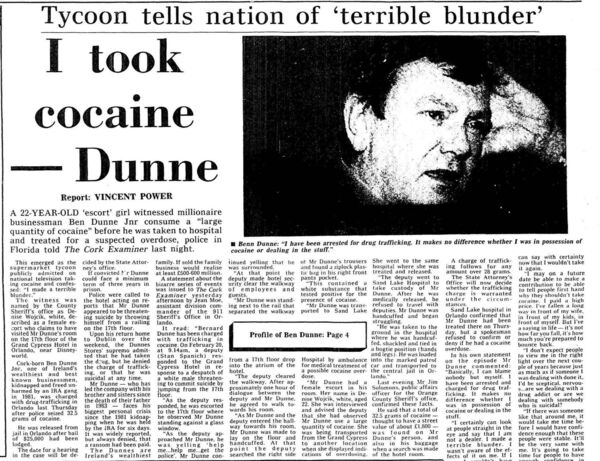

Nine years later, in February 1992, onlookers in the lobby of the Grand Cyprus Hotel in Florida would have seen a man hogtied to a pole being carried out the door by a number of police officers. In that instant, one might well have asked Dunne where it had all gone wrong.

He had just been arrested after an escort he had hired, Denise Wojcik, thought he was going to throw himself off the balcony of his 17th floor hotel room.

The tycoon had consumed enough cocaine to floor a horse.

Once he was released and returned home he gave an interview that was pregnant with humility and regret. That he would attribute his descent to the trauma he suffered from the kidnapping was convenient but was also quite obviously rooted in fact.

The fallout from that episode ensured that Wojcik would go down in history as having played a major role in rooting out a culture of corruption that had persisted for decades.

Dunne’s sister Margaret Heffernan and brother Frank were appalled at the publicity around Florida, feeling it had dragged the family name into the gutter.

They ousted him from Dunnes Stores and in doing so filed legal papers which alleged he had given huge sums of money to Charles Haughey.

That in turn led to the unmasking of Haughey as having received over €8m in donations from various wealthy interests in the course of his political career.

Two tribunals ensued at which Dunne was a major figure.

The main one, presided over by Judge Michael Moriarty, found that Dunne was corrupt. He never accepted the verdict but the reality was that he had played a role in ensuring that the elected leader in a democracy was a kept man, in hock to wealthy interests.

Ben Dunne had no regrets about funding Haughey. “I gave him money and you have to get on with your life,” he told Miriam O’Callaghan.

He was just helping a man who needed a dig out.

Through his eyes it was entirely transactional, a businessman making a decision just as his father had done so in paying a ransom to his kidnappers.

He went on to have a second life in business after Dunnes Stores, opening a chain of gyms that brought low-cost fitness to the masses just as his father had brought low-cost groceries. He never saw his role in funding Haughey’s lifestyle as corrupt.

If it wasn’t for his redeeming features, Dunne could have been a very unpopular figure in Irish life. But he did have humility, he was well liked and he was capable of the kind of empathy that is often beyond the very wealthy and very powerful.

He had suffered his own trauma and learned from it slowly, painfully. He knew shame and was aware of how fortune had ultimately smiled on him.

He lived life large and departed a bit too early, but through his travails he was an unwitting agent in exposing the sullied interface between business and politics that might otherwise have been sealed forever.

A collection of the latest business articles and business analysis from Cork.